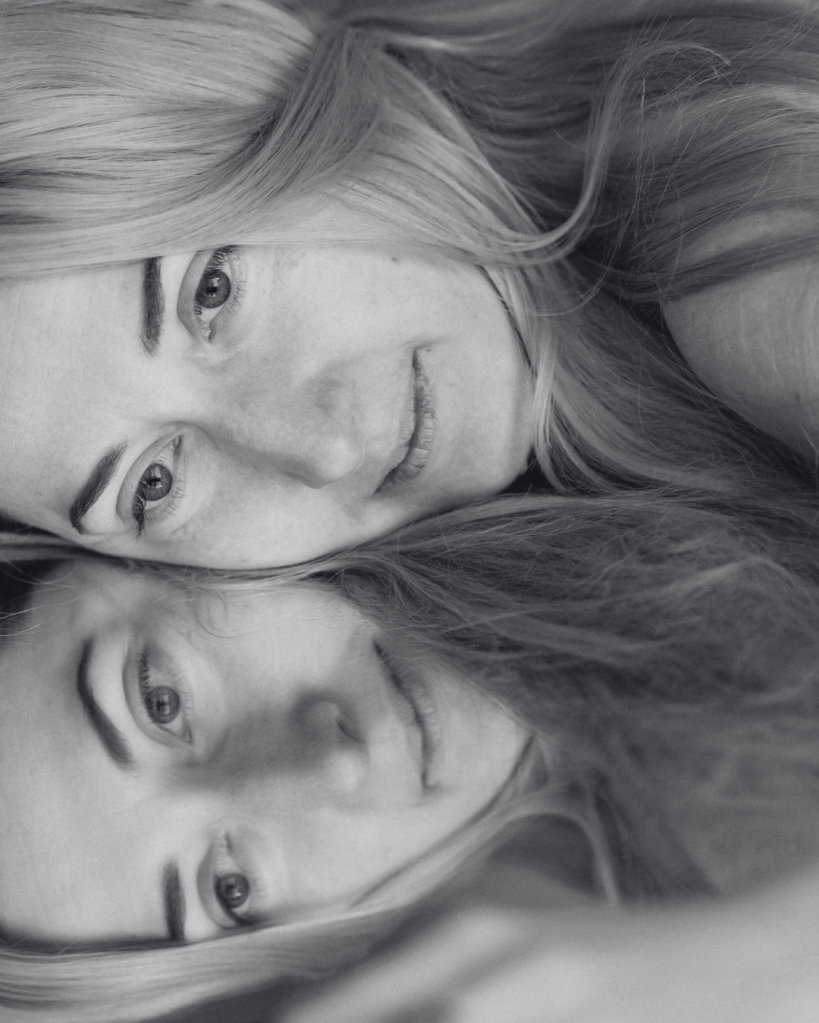

I am not what you think I am, you are what you think I am

There’s a delightfully uncomfortable truth lurking in the background of every human interaction, and it goes something like this: the version of me that exists in your head has sod all to do with me, and everything to do with you. Your brain is essentially a narcissistic film director, casting me in whatever role suits your internal narrative, whilst I stand there entirely unaware I’ve been given lines I never auditioned for.

Welcome to projection, that glorious psychological defence mechanism where we fling our own thoughts, feelings and unresolved bollocks onto other people like emotional confetti. Freud banged on about it, and whilst the old cocaine enthusiast got plenty wrong, he absolutely nailed this one. We don’t see people as they are. We see them through the grubby lens of our own experiences, biases, and that one incident in Year 9 when someone vaguely similar made us feel rubbish.

The Comprehension Gap Nobody Mentions

Let me paint you a picture from my own mildly bewildering existence. I write things. Clear things. “I live in a Land Rover. I’m a writer and wilderness guide. And I wrestle stones for sport” levels of clear. And yet I’ll receive comments that suggest the reader has either suffered a minor stroke halfway through, or is responding to someone else’s work entirely. It isn’t malice. It’s the comprehension gap, that yawning chasm between what I’ve written and what they’ve understood once it’s been filtered through their particular cognitive soup.

Research on reading comprehension shows that we don’t passively absorb information like polite little sponges. We actively construct meaning based on our existing knowledge, vocabulary and cognitive capacity. When someone with limited experience of a subject reads expert level content, they’ll often latch onto familiar fragments and build an entirely new narrative around them, blissfully unaware they’ve just erected a sandcastle whilst reading architectural plans.

Intelligence differences compound this rather beautifully. Not the “I did well on an online IQ test” variety, but genuine differences in cognitive processing. Someone operating at a different cognitive level isn’t being stupid, they are literally experiencing a different reality. The same paragraph that reads as a nuanced exploration to one person reads as contradictory nonsense to another because they’re working with different processing equipment. Expecting otherwise is a bit like asking a Nokia 3310 to run the same software as an iPhone.

The Romantic Projection Spectacular

Relationships, particularly romantic ones, are projection’s natural habitat. I’ve had the peculiar experience of being exactly who I said I was, wild living, stone lifting psychologist with a fondness for Land Rovers and brutal honesty, and still managing to surprise people when I turn out to be precisely that. Live videos? Check. Meeting me in person? Check. Bewildered expressions when I deadlift something heavy or bivvy by a loch? Also check.

What’s happening here isn’t mystical. It’s the idealisation phase of attachment theory doing its sparkly little dance. Research by Murray, Holmes and Griffin shows we don’t fall in love with actual people. We fall in love with our positively distorted perceptions of them. Your brain creates a highlight reel, glossy, heroic, soundtracked like a Netflix trailer, edits out the inconvenient bits, and plays it on repeat until reality arrives like an unwelcome bailiff.

When someone says they “thought you’d be different”, they aren’t necessarily lying. They genuinely did think that, because they weren’t dating you. They were dating their projection of you, dressed in your clothes and borrowing your face. When the real you stubbornly persists in being yourself, cognitive dissonance kicks in. Rather than rewrite their internal screenplay, they blame you for not matching the character they invented.

Sometimes, of course, they are lying. Let’s not be wildly optimistic. Some people actively misrepresent themselves, and that’s a different psychological circus entirely. But even with someone genuinely authentic, projection does its work regardless.

Demographics of Delusion

Here’s where things get properly messy. We’re not just projecting individual neuroses, we’re projecting entire demographic assumptions. Gender is a classic example. Research consistently shows identical behaviour is interpreted differently depending on who’s doing it. A confident man is “assertive”. A confident woman is “aggressive”, “bossy”, or “a bit much”. Same behaviour, different projection screen.

Money adds another layer of interpretative chaos. Tell someone you live simply by choice rather than necessity and watch two entirely different stories unfold. One version is “minimalist” and “authentic”. The other is “struggling” and clearly needs “help”. Same caravan, wildly different conclusions. Your actual circumstances matter far less than what the observer’s background primes them to see.

Religion and culture bring their own filters. I can write “I value stillness and introspection” and be interpreted as spiritual, depressed, or just plain weird, depending on the reader’s framework. None of these interpretations required my input, and none come particularly close to the truth. The meaning exists entirely in the space between their eyes and my words.

Life experience might be projection’s most potent ingredient. Someone who has never experienced profound loss reads my writing about grief very differently to someone who has. Not better or worse, just differently. They aren’t reading the same essay. They’re reading through entirely different experiential lenses, each finding meanings the other simply can’t access.

Platonic Projections and Professional Puzzles

Friendships aren’t immune to this psychological puppet show. That friend who’s disappointed you’re “not fun anymore” may well be projecting their own fear of ageing onto your entirely reasonable decision to stop getting absolutely wankered at 3pm on a Tuesday. The friend who says you’ve “changed” often means you’ve stopped matching their projection, which has remained frozen in 2015 whilst you’ve had the audacity to evolve.

Then there’s the unsolicited advice, which lands like a wet fish because it isn’t actually for you. I’ve stood there more times than I can count listening to pop psychology delivered with great confidence and very little relevance, thinking, “Have you met me? Do you know anything about my actual life?” The answer is usually no. They aren’t advising you. They’re advising themselves, using your situation as a convenient vehicle for working through their own unresolved nonsense.

Someone who’s never lived rough tells you about “stability”. Someone terrified of being alone insists you “need to put yourself out there more”. Someone who’s never experienced loss offers platitudes about “moving on”. They aren’t seeing you. They’re seeing their fears, their assumptions, their internal chaos, and calling it concern.

Professional relationships add their own special flavour. Clients project competence or incompetence based on everything except actual competence. Accent, gender, how much your expertise makes them feel exposed. I’ve watched people dismiss research backed approaches because they clashed with what their cousin’s neighbour once said about healing. Not evidence. Just projection in a lab coat from Amazon Prime.

The Troll Tells All

And then there’s trolling, that exquisite art form where someone broadcasts their internal wasteland whilst believing they’re commenting on yours. Every nasty comment is a confession. “You’re ugly” translates neatly to “I feel inadequate about my appearance”. “Nobody likes you” usually means “I’m lonely and furious about it”. It’s projection in its purest form, a psychological selfie they’re too dense to recognise.

Research on the online disinhibition effect shows anonymity doesn’t create new thoughts. It simply removes the filter. The viciousness was already there, quietly fermenting. You just happened to wander past while they were looking for somewhere to dump it.

The Uncomfortable Liberation

Once you grasp that other people’s perceptions are their projections, not your reality, something quietly radical happens. You’re free. Their disappointment that you’re not who they imagined? Not your problem. Their insistence that you’ve “changed” when you’ve simply stopped performing? Still not your problem. Their elaborate fantasy based on three Instagram posts and a blog they skimmed? Absolutely not your problem.

Even their advice that sounds like they’ve never met you, though admittedly harder to endure politely.

This cuts both ways. Your perception of them is also contaminated. The person you think is perfect has been idealised. The one you can’t stand probably has your unresolved issues projected onto them. We’re all blundering through a hall of mirrors, occasionally catching a glimpse of an actual human between the distortions. This is why therapists have supervisors. It’s also why we paraphrase. “What I’m hearing is…” followed by giving the other person a chance to correct us, instead of confidently misunderstanding them and charging ahead.

The healthiest relationships happen when both people accept that projection is inevitable and commit to checking it. “Is this actually them, or is this my baggage?” becomes a regular audit. It isn’t romantic. But neither is blaming someone for failing to live up to a fantasy you wrote without their consent.

Reality as a Radical Act

Being exactly who you say you are is, oddly, a revolutionary act. People aren’t used to consistency. We’re swimming in curation, performance and strategic positioning. Authenticity unsettles people because it doesn’t fit their projection patterns. They keep waiting for the reveal, the moment you admit you’re not really living in the woods, lifting stones, or being blunt about psychological research.

The reveal never comes, because there isn’t one. But brains trained on deception keep looking for the trick. Your consistency feels suspicious because they’re projecting their own duplicity onto you.

So here we are. I am not what you think I am, because what you think I am exists only in your head, assembled from your experiences, filtered through your biases, and decorated with your projections. I’m just here, being exactly what I’ve always said I am, whilst you direct your internal film with me as an unwitting star.

The question isn’t whether projection happens. It’s whether you’re aware enough to recognise your own. Most people aren’t.

Leave a comment